What Do We Owe Each Other?

- Michelle Agatstein

- Aug 4, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 25, 2025

When the COVID-19 outbreak was first reported, the Korean government initiated a communication campaign that Koreans accepted with near unaminity. (You can read about my experience here.) Masks were in full fashion. Streets were bare. Foot traffic ebbed and flowed for a couple months. Businesses struggled. Many people lost their jobs. Other businesses pulled through, like, fortunately, my for-profit academy. Innovative thinking and quick adaptation was a must.

Koreans flattened the curve before that phrase meant anything to the world. Other countries, like the USA, adopted efficient Korean testing procedures, such as drive-thru testing facilities. Many people attribute Korea's successful response and results to the changes the country and its government made after realizing the failures to quickly contain coronaviruses SARS and MERS. I was (and still am) new to a collectivist culture, and I wondered how much of this sociology contributed to the success of the COVID-19 containment, as well.

There's research to suggest that a collectivist mentality is helpful in containing the spread of the virus. In many countries with low rates of virus transmission, trust in government was high, and so were the testing rates. Take, for instance, New Zealand and its very low rate of coronavirus cases. According to that linked article, the main points attributed to their success were a firm lockdown, effective communication from government (via text message, just like in Korea), testing efficiency, and geography.

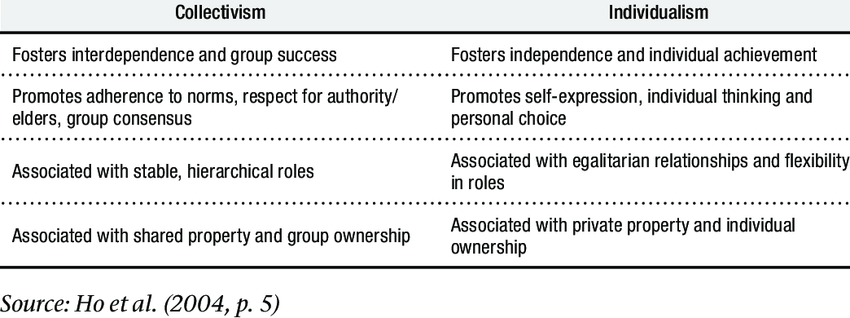

New Zealand is an individualist culture. You may be wondering: individualist vs collectivist -- what's the difference? Please allow me to break the answer into a few simple visuals:

Traits of Individualist Cultures source Traits of Collectivistic Culture source Collectivism vs Individualism source

Remember that collectivist mentality research study I mentioned and linked earlier? It suggested that having a collectivist attitude helps a society to move forward in a positive direction together. It suggested not a systematic change to a society's culture, but merely the adoption of a collectivist mindset.

I remember the changes that clicked into place so suddenly in February, when Korea began responding to the medical threat. Yes, masks were already a thing, but suddenly everyone was wearing them. People mostly stayed in their homes. While self-quarantining, I saw minimal foot traffic outside my window. My view toward the typically busy mall and subway station afforded me a count of perhaps five people each day (whenever I was paying attention, but I was sure bored at home and willing to count other humans when there was nothing else to do). Emergency text messages were flooding in every day from the Korean government, advising how to wash your hands, stay home as much as possible, and detailing anonymous positive COVID cases and the previous whereabouts of those individuals.

I remember wondering how this would all work in American society. Would it fly? Would people adopt to the drastic cultural change? Could this only work in a collectivist culture? Could American people come together to defeat this common invisible enemy?

We have seen answers to these questions on a global scale, and from that sociological perspective, it's certainly been interesting.

But it has felt personal to me. "Interesting" is such an easy word to use to describe the situation. It is also so impersonal and removed.

Allow me to switch gears from the objective, scientific, research-ridden logos from which I've begun. Let's ride a wave of pathos for a moment, and please pardon my ego.

Does April feel like a long time ago? Can you remember what was happening then? There have been so many changes between then and now. The US lock-down began around late March/early April, and I remember having conversations with friends and family, who still had doubts about the coronavirus, confused by misinformation and rumors swirling about the internet. They'd heard of COVID-19 affecting Asia, but was it even real? Was it a hoax perpetuated by China? Was it a hoax perpetuated by the American government? Was it as serious an illness as scientists said?

I heard and read a lot of these questions on social media when the news of corona hit my western demographic on Facebook. (Unfortunately, I still do today.) I saw some beautiful, perhaps Panglossian (shout-out to Dumas) optimism that perhaps the virus wouldn't be that big of a deal. Perhaps there wouldn't be that many cases. Perhaps it would all just go away.

My academy had closed late February, around the time masks became more ubiquitous than usual. By the time the west was waking up, Korea had already "flattened the curve" and had a second wave of outbreaks, one of which I'd been tested for. My friends and coworkers in Korea were watching the rest of the world (and still are now) with wide eyes from the comfort of our very fortunate geography. Korea's government wasn't perfect, but the reaction was swift. Koreans weren't perfect, but they were largely respectful and willing to follow guidelines for the good of society and its people. Is that because of Korea's history? Is it because of trust in authority? Is it because Koreans value their elderly more? Is it because of a collectivist culture? A more optimistic view of the future? A cultural and digital divide from the side of the world that consistently perpetuates conspiracy theories? The aggressive academic system? I don't know. I know that I felt an immense burden on my shoulders. I remember crying multiple nights because thousands of people were going to die, and I couldn't do anything about it. It was like watching a bad sci-fi medical thriller. My boyfriend urged me to write about it, to express my thoughts and feelings to the world. I was a bit paralyzed by overwhelm. Those of you who know me know that I tend to be agreeable, not ruffle any feathers. My go-to is either a smile or humor to lighten the situation.

I responded to my Panglossian friends as honestly as I could, but the negativity felt so wrong. "It's not going to go away. Lots of people are going to die," I said a few times. Dang, Michelle, way to keep the mood light, right?

But it was the truth, and I'd seen it time and time again in other countries. My coworkers from South Africa, Italy, New Zealand, and Canada were watching it happen in their countries, either exploding in flames or fortunately extinguishing, region-depending, in a race that is very unfortunate to watch. A race that you can't help but rubberneck, especially since it hits so close to home.

I mean, even if you have that very terrible, foreboding feeling, what can you do? "Watch out! Your car is about to crash!" "Oh, no! Mt. Vesuvius is about to blow!" "Egad! Your government is about to confound millions of you to hapless infection!"

It was a feeling of powerlessness, and I'm sure you felt it, too. Scrolling through social media is a doozy in 2020, let alone any election year. There's so much negativity, and I have always identified with the personal brand of "sunshine all the time." I didn't want to add to the pessimistic rhetoric that so many browse Facebook to escape.

But here we are. Things are rough. Things are bad. Things are going to get worse.

So, where's that sunshine? I always believe in a silver lining.

I suppose the sunshine comes from this: We have power, the collective all of us. There's strength in numbers, they say. And this time, there's strengthen in digital numbers. (Socially distanced strength!)

There was a recent Forbes article that poses that Americans are perhaps already embracing a more collectivist mentality. No, we won't be abandoning our individualist culture anytime soon; it's too deeply tied to our identities as individuals and people. But you can already see the collectivism whenever you see a push against anti-maskers. The linked article talks about conformity, and there are indeed many American groups pushing for conformity one way or another, but in the age of corona, it's often individuals with an egocentric opposition toward mask-wearing vs. a large group of empathetic, rule-abiding people.

The keyword here is empathy. In an ideal world, the US would have a positive, effective, forward-thinking set of governments (we're talking federal to local levels) that could unite people around a common goal, much as has been done in successful COVID-responding countries. Coming from a background of marketing and sales, I understand the power of marketing and PR. "Buckle Up." "This is your brain on drugs." "Keep calm and carry on." "Don't mess with Texas." Those are the efforts of positive marketing campaigns led by governmental and non-profit organizations. (Yes, the Texas one was a marketing campaign against littering.) They resonated with the public for the greater good. Where's the positive coming-together of creatives in government these days? Where's the "Relax; Wear a Mask" campaign? (I know you guys can do better than me on this. Come on!)

I've been sleeping on more philosophical questions lately regarding cultural shifts and human responsibility.

It broadens beyond just COVID-19, too, though, yes, this has been the centerpiece of my quandaries here. Taking into consideration ongoing civil rights movements (from Black Lives Matter to Chinese internment camps), climate change, the responsibility and accountability of social media (Facebook privacy concerns, TikTok privacy concerns, Cambridge Analytica--oh, sorry: Data Propia and Auspex International), I have many new questions, such as:

Which will grant us the most ethical future: individualism or collectivism?

Which will grant us the most sustainably prosperous future?

What do we owe to our fellow man? To our planet? To the future generations who will walk in the wake, whatever may blossom or turn to ash?

What do I personally owe my neighbor?

Should the government bear more of the burden of responsibility than the individual?

Should the world's problems be solved by collections of people, rather than individuals, be they within non-profit organizations, corporate entities, or municipalities?

Should a corporate entity be tasked with carrying the weight of the torch for their customers, much in the way that governments are expected to carry the weight of the torch for their constituents?

And if it is an institution's responsibility, in any capacity, to solve the problems in our world, then how can we hold them properly accountable if they fail?

Are Americans making a dent, yet, after enacting straw bans?

How can I better listen to others?

How can I take all these balled-up emotions and all the knowledge I'm learning from others and convert it into ACTION?

I read a post on r/ShowerThoughts (reddit) recently that posed this idea: The more we learn, the more questions we have.

I have a lot of questions.

What about you?

Comments